Ricardo de Oliveira Orsi, Professor, Department of Animal Production and Preventive Veterinary Medicine, School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science (FMVZ), São Paulo State University (UNESP), Botucatu, SP, Brazil.

The intensely defensive behavior of the Africanized honeybees Apis mellifera annually promotes several fatal accidents involving humans and animals. This is mainly due to the presence or migration of colonies in urban or rural areas1. In order to reduce the mortality of patients envenomed by multiple stings, the multidisciplinary team of the Center for the Study of Venoms and Venomous Animals (CEVAP) from the Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), São Paulo, Brazil, developed the new apilic antivenom (AAV)2, 3, 4.

The intensely defensive behavior of the Africanized honeybees Apis mellifera annually promotes several fatal accidents involving humans and animals. This is mainly due to the presence or migration of colonies in urban or rural areas1. In order to reduce the mortality of patients envenomed by multiple stings, the multidisciplinary team of the Center for the Study of Venoms and Venomous Animals (CEVAP) from the Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), São Paulo, Brazil, developed the new apilic antivenom (AAV)2, 3, 4.

For the collection of apitoxin aiming at AAV production, it is necessary the correct management of apiaries for this purpose, with the development of a standard operating procedure. For this, some points are important, starting with the use of standardized materials and equipment. Honeybee colonies can be obtained by capturing native bees that are nesting in different places, such as trees and urban areas; capture of migratory swarms, which is a natural process of honeybees and a form of expansion of the species; or division of existing colonies in the apiaries.

After capturing the bees, it is essential that the beekeeper provides the minimum conditions suitable for the good development of the colony. Thus, it is necessary: to change the hive frames containing old wax combs for new ones (those that are rejected by the egg-laying queen); to assess the presence of infectious or parasitic diseases; to evaluate if the queen laying pattern is homogeneous (in relation to the queen physiological age according to Figure 1A); to assess the presence of stored food, which include nectar that provides energy, and pollen that is a source of protein. Bees have special nutritional requirements for their adequate development which can be provided by beekeepers in the off-season using alternative foods5, 6. The article Energetic supplementation for maintenance or development of Apis mellifera L. colonies published in the Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases5 offers further information on bee food sources.

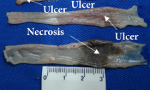

Once the colony is established and the appropriate technical management is applied, the collection of apitoxin can be carried out in hives containing at least six laying frames. This guarantees a minimum number of worker bees necessary for adequate and abundant production of apitoxin. The recommended collector is the electric one (Figure 1B) based on the principle of generating a small electric current. This, when properly applied, promotes contraction of the accessory muscles of the sting apparatus, causing the apitoxin stored in the reservoir to be released into the collector. As there is no sting itself, worker bees do not die from the loss of the stinger and thus high mortality in the colony is avoided. The morning period is the most suitable, usually around 9 a.m. The ideal collection time is approximately one hour, as this interval showed the lowest expression of stress-related genes in Africanized worker bees, culminating in higher apitoxin productivity7. It is recommended to repeat the collection every 42 days, thus respecting the average life of worker bees.

Image: authors.

Figure 1. (A) Frame containing an example of homogeneous laying of eggs by the queen and (B) an electrical collector of apitoxin.

After the collection of apitoxin, it must be handled following standard operating procedures to avoid any type of intoxication by the handler8,9,10. It is recommended to handle apitoxin inside laminar flow chambers, using personal protective equipment, such as disposable latex gloves, goggles, masks and disposable aprons. Then, the collected material, which contains the solid phase of apitoxin and possible undesirable dirt, must be scraped from the glass plate with the aid of a sterile blade and then placed in amber containers (plastic or glass). When collected, this raw material must be diluted in saline solution and centrifuged. Then, the supernatant (which contains the apitoxin) must be removed, filtered through disposable filters, aliquoted and stored in a freezer at –20°C to preserve its biological properties. As it is a biological material, the collection of apitoxin must respect the technical recommendations described above, thus ensuring the production of pure and quality biomolecules for research and production of antivenom.

Read more

- ZALUSKI, R., et al. Africanized honeybees in urban areas: a public health concern. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical [online]. 2014, vol. 47, no 5, pp. 659-662 [viewed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0254-2013. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/rsbmt/a/prjgGkDBBTmvcx3GrXWVvVR/

- BARBOSA, A.N., et al. A clinical trial protocol to treat massive Africanized honeybee (Apis mellifera) attack with a new apilic antivenom. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases [online]. 2017, vol. 23, no. 1 [viewed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40409-017-0106-y. Available from: https://jvat.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40409-017-0106-y

- TEIXEIRA-CRUZ, J.M., et al. A novel apilic antivenom to treat massive, Africanized honeybee attacks: a preclinical study from the lethality to some biochemical and pharmacological activities neutralization. Toxins [online]. 2021, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 30 [viewed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13010030. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/13/1/30

- BARBOSA, A.N., et al. Single-arm, multicenter phase I/II clinical trial for the treatment of envenomings by massive Africanized honey bee stings using the unique apilic antivenom. Frontiers in Immunology [online]. 2021, vol. 12 [viwed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.653151. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.653151/full

- OLIVEIRA, G.P., et al. Energetic supplementation for maintenance or development of Apis mellifera L. colonies. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases [online]. 2020, vol. 26, e20200004 [viewed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-9199-jvatitd-2020-0004. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/jvatitd/a/YYcHndpTphhbVrt9Fc5jbZJ/

- CAMILLI, M.P., et al. Protein feed stimulates the development of mandibular glands of honey bees (Apis mellifera). Journal of Apicultural Research [online]. 2021, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 165-71 [viewed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2020.1778922. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00218839.2020.1778922?journalCode=tjar20

- MODANESI, M.S., et al. Period and time of harvest affects the apitoxin production in Apis mellifera Lineu (Hymenoptera: Apidae) bees and expression of defensin stress related gene. Sociobiology [online]. 2015, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 52-55 [viwed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.13102/sociobiology.v62i1.52-55. Available from: http://periodicos.uefs.br/index.php/sociobiology/article/view/470

- ALMEIDA, R.A., et al. Africanized honeybee stings: how to treat them. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical [online]. 2011, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 755-761 [viwed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0037-86822011000600020. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/rsbmt/a/kfT6PJqFyjhVqhSQPPThxgd/

- FERREIRA, R.S., et al. Historical perspective and human consequences of Africanized bee stings in the Americas. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B [online]. 2012, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 97-108 [viewed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.1080/10937404.2012.645141. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10937404.2012.645141

- PUCCA, M.B, et al. Bee updated: current knowledge on bee venom and bee envenoming therapy. Frontiers in Immunology [online]. 2019, vol. 10 [viwed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02090. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02090/full

To read the article, access

OLIVEIRA, G.P., et al. Energetic supplementation for maintenance or development of Apis mellifera L. colonies. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases [online]. 2020, vol. 26, e20200004 [viewed 6 June 2022]. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-9199-JVATITD-2020-0004. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/jvatitd/a/YYcHndpTphhbVrt9Fc5jbZJ/

Link(s)

Instagram: @nectar_unesp

Social Media – JVATITD: Facebook | Twitter

Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases: https://www.jvat.org/

Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases – JVATITD: https://www.scielo.br/j/jvatitd/

Como citar este post [ISO 690/2010]:

Recent Comments